by Paul Simpson — Dec 12, 2022

How do you reset an organisation when everyone in it is stretched to the limit on one of the world’s most ambitious, biggest and most complex infrastructure investments? That was the challenge facing Kate Hall in August 2021, when she took over as project director at Design House, a joint venture between Arup, Typsa and Strabag, managing the delivery of the high speed railway HS2 on the approaches to a completely new terminal at London Euston.

Even in an ordinary line of business resetting an organisation’s processes, culture and mindset can be tough but Design House’s was no ordinary line of business. It was, in Hall’s words, a “mega project, not a major project.” She adds, “When I arrived, the team had already been slugging it out for more than four years and it was hard to see how they could maintain that over the months and years ahead unless something changed. They were knackered, demotivated and didn’t have much downtime to think about how things might be done differently.”

Managing 43km of HS2 from West Ruislip to Euston, Design House’s remit was both incredibly detailed and very broad. The company was responsible for designing everything from major tunnels and caverns – including deep shafts and excavations, mined audits and cross passages, civil engineering, highways, bridges, structural, geotechnics, architecture, fire, mechanical and electrical services – to carbon assessment, aerodynamics and acoustics. The joint venture employed 1,200 staff (most of them engineers) across 22 locations (not counting remote working, hybrid working and home working) spanning different cultures, languages and time zones.

The pressure on the team was relentless and the perception that their efforts were going unrecognised was leading to miscommunication, siloing of information, lack of collaboration and territorial thinking. Left unchecked, such behaviour could impair performance. This was why, as Hall points out, “they needed something radically different.” Design consultancy DK&A, parent company of the Design Thinkers Academy London, embarked on a partnership with Design House to figure out what changes could be made.

Designing a service, not a product

“Design is agnostic of any solution,” according to David Kester, founder of DK&A, who led this project alongside Design House.

When you are designing an object – whether it be an office chair, a little black dress or a computer game – the consequences of the choices you make soon become apparent, tangible and visible. When you are designing a service – be it to provide social care, an airline check-in system or manage a project – the process is much more opaque. The solution will probably involve a mix of digital, physical and interpersonal assets, each of which need designing and each of which needs to form part of a cohesive whole. This makes it much tougher to envisage likely outcomes, especially at the very start.

Effective service design relies on five core principles:

- User-centricity. Qualitative research is essential to ensure that the designed solution meets all user needs.

- Co-creation. It is imperative that all stakeholders actively contribute to the design process.

- Sequencing. For complex services, designs will probably need to be separated into different sections and user journeys.

- Experiencing. The design needs to be made tangible to help users understand it and give feedback.

- Holistic. Every touchpoint (experience, interaction, user, network and location) needs to be designed.

This sounds complex because it is; there are many ways the process can go wrong. “As innovators, we often say that the last thing we do is design. We don’t start with solutions, instead we start with understanding the unmet needs of the user” says David.

Simon Gough, DK&A’s Associate Service Design Director on the project, elaborates on this point: “You can come up with the right solution for the wrong problem. Given time pressures, there is always a temptation to rush to conclusions – and solutions – which can make people reluctant to compromise on their favourite concept. And there is always a risk that, despite the best intentions, the process ends up being driven by particular users’ needs which will make the solution less effective.”

Drilling down

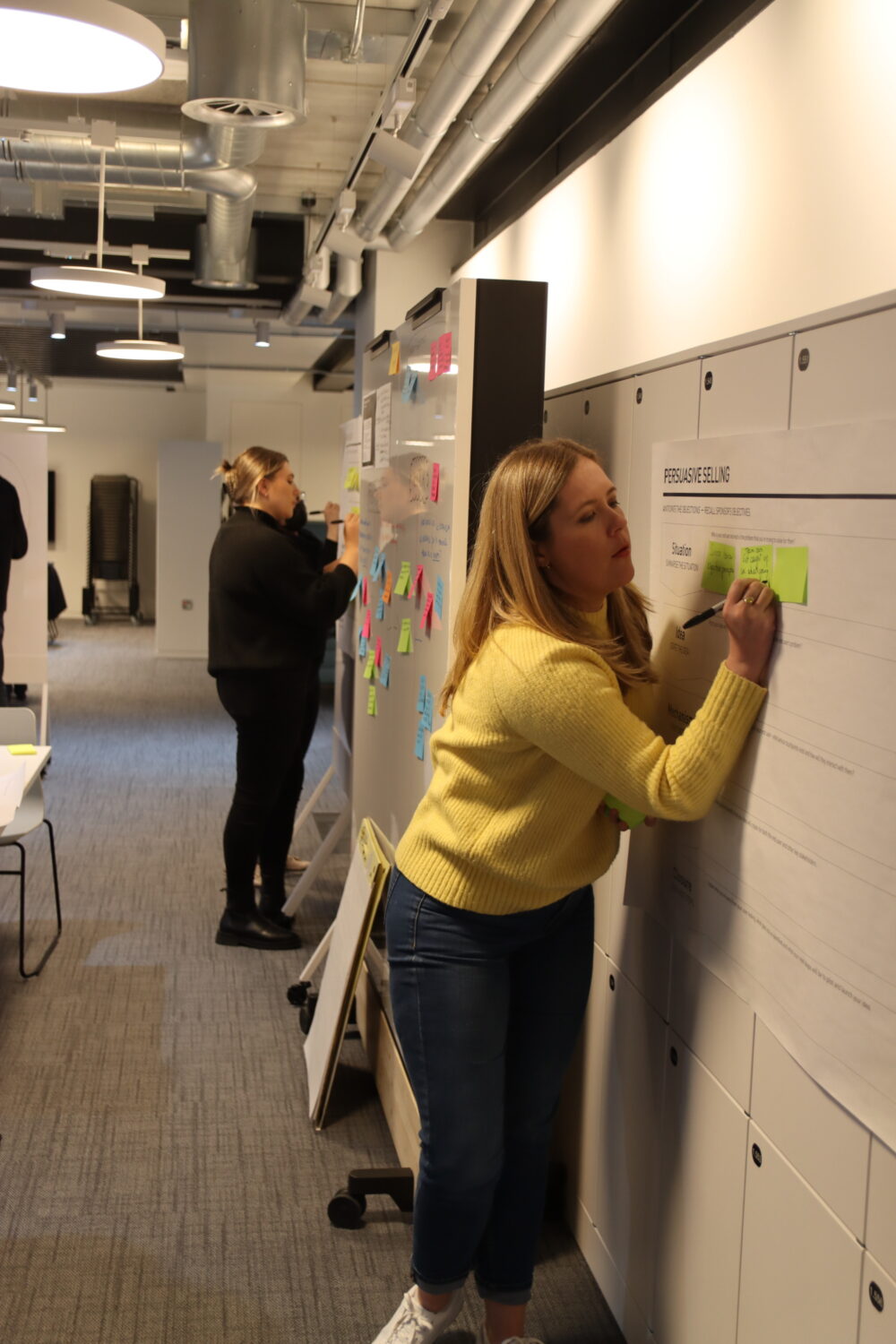

DK&A started their work by facilitating a collaborative innovation approach, putting Design House employees and leadership at front and centre of the process. A research discovery phase kicked off the project, mixing a range of ethnographic research techniques, including interviews with key stakeholders and quantitative surveys with employees. This was crucial to uncover the true employee experience at the heart of Design House and the root and cause of a lot of the problems that were being experienced.

One of the first issues faced was around company culture. “Some of the staff came from an engineering background,” says Anna Holiday, People and Organisations Manager at Design House, who was a member of one of the internal teams that drove the project. “And the process required a different style of thinking and mindset for some people. You don’t have to have the answer to every single question. It is about discussing the question as a group to explore your thinking.”

In engineering, as in product design, there are detailed rules that define good and bad practice. With service design, especially early on, it is harder to evaluate ideas and envisage outcomes, so debate needs to be as wide-ranging, open and collaborative as possible. “Different teams and people work at different speeds,” says Gough. What looks effective in the short run – making decisions quickly – may prove counterproductive in the long run. Sometimes, keeping a variety of outcomes in play can pay dividends later on.

“Sharing work that’s a long way from finished – work that’s just the starting point or about a single aspect of what we’re aiming for – is a crucial part of working with other people.” adds Gough. “Sharing this work is vital to a collaborative, iterative process, so different from the binary of success and failure – and that requires trust that other people can make your ideas better.” In many cases, he says, people don’t feel they have the permission to do this and strive for perfection – or just don’t share.

At Design House, such concerns soon faded as the process gained momentum, deepening collaboration and innovation. “People understood that design thinking could help them acquire new skills,” says Holiday. “For example, they quickly realised the value of stepping back right at the start of a project to take a broader view before focusing on a specific aspect of the solution.”

“Design thinking is a methodology,” says Hall, “but DK&A’s designers are very good at taking the time to learn and listen so people felt they were being upskilled and acquiring a virtual briefcase of tools they could use in their jobs.”

Gough explains the approach in more detail:

“The process was driven by ‘learning from doing’ right from the start. Every colleague from Design House was on an explicit learning journey, understanding how to use design thinking for collaborative innovation. Our designers were integrated into their teams so that we could act as coaches and offer expert advice when required.”

Creating solutions

During the course of the discovery phase, it became clear that a core problem facing the HS2 project was employee wellbeing. The already “mega” nature of the project, combined with the disruption of the coronavirus pandemic had stretched people across all departments and this was impacting the work Design House were trying to achieve. By listening to people from all parts of the project, a central focus had been discovered around which solutions could be devised.

Collaborating with the senior leadership team, DK&A & Design House’s research was used to create some immediate practical initiatives that could help improve processes and productivity, increase levels of collaboration, raise morale, and – most importantly – improve employee wellbeing. David said:

“Training and coaching a small team from Design House as in-house ethnographers, meant that the research findings were wholly owned by the three companies in the consortium.”

This first meant management recognising the many problems that arose from the research and initiating a re-set moment with an agenda for change – one branded by DK&A. The senior leadership then attended a week-long course on managing collaboration on-line, with a focus on how different and challenging it can be for groups to work together on a project post-pandemic. Then an improved induction for new team members was built to improve the onboarding process and create a far stronger sense of team and unity.

The final aspect was an ambition to co-create a recognition scheme that could raise morale, increase motivation, and support staff’s mental well-being. This needed to cater to everyone, as Gough notes, “it was important we didn’t design a solution that just recognised the engineers’ achievements. Every function within the organisation needed to feel valued.”

Using the initial research, the work first centred around a challenge statement; a north star for the whole project to revolve around as potential solutions were explored:

“How might we… run our own team recognition programme that celebrates the work of Design House and its contribution to our national infrastructure?”

The birth of Kudos

Using the challenge statement as a springboard the Sprint programme then moved into action. Collaborating both online and in-person, it involved 15 Design House employees split into various teams. They were led by DK&A through the design thinking double diamond process, identifying insights and guiding principles for the project, before carrying out further research. An all-day workshop followed, involving the senior leadership team. There the teams began forming their respective ideas which were then developed throughout the course of the Sprint.

To keep the process focused, DK&A used a method called service blueprinting, which Gough describes as a “map of a complete service over time, including all the people and systems who help to deliver it. It is designed around the actions of the user or customer to make sure it focuses on their experience.” The key elements of the blueprint are demonstrated visually to participants with storyboards and process diagrams, and it is updated continually in response to feedback from users and the results of prototyping.

The approach to service blueprinting will vary according to the organisation’s needs. As Gough says: “For some, service design means defining a whole new vision but in other cases, the goal is to innovate within an existing service.” Since the pandemic-induced shift to remote, online and hybrid working, building a service blueprint has become even more crucial in keeping such complex processes on track.

For Hall, during the process two things soon became apparent: recognition was a prime concern for staff and that their preferred method of recognition varied widely: “Not everybody wants a bottle of champagne. For some people, it’s more important their efforts are appreciated by the people they work with, for others a conversation over a coffee with a senior leader is more of an incentive.”

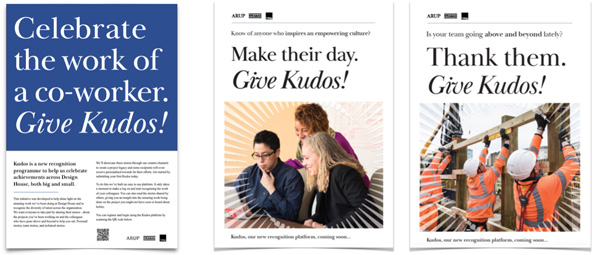

This all led one central idea: an internal employee recognition platform called Kudos.

Kudos was designed to encourage staff to share positive feedback and let the organisation’s leaders know when their interaction was required. “There is no point in senior leaders sitting down with each other and saying ‘this is what people want,” says Holiday. “To be truly valuable, recognition programs need to be co-created, collaborative and inclusive.”

After settling on the idea of Kudos – using design tools including service blueprinting, storyboarding and user-flows – user testing began. This meant actively going out and speaking to the people who would use Kudos to see where it worked, where it didn’t and where it couldn’t be improved. Once that guided the concept further, prototyping followed, running a series of experiments where each element was tested. Then finally there was the branding, done by DK&A, delivering Kudos as a complete programme that could be adopted immediately by Design House.

Kudos in practice

Because of the collaborative way Kudos was built, with its focus on – and input from – all levels of the team, the Kudos recognition system encourages employee engagement, team spirit, collaboration and innovation. The design process has already strengthened connections across a company where work is, of necessity, segmented among so many teams, specialisms and areas.

It’s early days for Kudos, but it is an essential part of ensuring that employee wellbeing is prioritised at Design House and that nobody’s contribution is lost in the noise of such a vast project. Ensuring not only that staff are rewarded for their efforts, but that rewards are not ‘one-size-fits-all’ and every individual can choose something they will personally value and enjoy is a key strength of the service – and one unlikely to have emerged without the extensive period of design research carried out by DK&A in partnership with Design House.

Reflecting on the project as a whole, David remarks, “In the eye of the storm, when a business is at maximum pain, design thinking is a go to approach. Why? Because it’s fast, collaborative and builds the right solutions based on need as well as the practical and commercial realities.”

Kudos has now launched and scaled across Design House’s operations. Kate Hall concludes, “it’s a fact of life that bad news travels much faster than good news. With Kudos we have created a mechanism for people to share good news, recognise when people are doing well and remind us all that, for all the pressures we are all under, we are achieving things that we could – and should – be celebrating.” And that very idea in itself, deserves its own little bit of kudos.