by Paul Simpson — Apr 29, 2022

Experiments are the engine of human progress. They has been for more than 5,000 years – ever since an inspired, but unknown lateral thinker in Mesopotamia discovered that the wheel, invented to make pots, could, stood it on its side with some spokes in it, serve as a mode of transport. The point that the right experiment, properly conducted, can be liberating, acting as an agent for positive change within society, an organisation and a company, has been reiterated countless times since.

That need to ask ‘What if?’ still propels us – it remains the driving force of modern science – but many of us work in organisations that, sometimes deliberately, often inadvertently, discourage curiosity, imagination and experimentation. The consequences of this failure are hard to measure – how do you quantify revenue you never earned or leaps forward that you never made? – but it seems logical to assume that it is putting the brakes on business growth.

In the past ten years, for example, companies on the American S&P 500 Index have grown their annual profits by an annual average of 3.4%, which is not much better than the rate of inflation (up 2.9% a year over the same period). That is hardly likely to endear CEOs to their investors – especially when the likes of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Tesla are growing exponentially faster.

Apples, prototypes, experiments and data

We tend to view experiments through the cliched prism of the apple falling on Sir Isaac Newton’s head, causing a ‘Eureka!’ moment that leads him to discover gravity (The apple did fall but not on his head). Many experiments are like that – physical tests that prove or disprove hypotheses – but they can also involve the creation of a prototype (as Herman Miller did with its revolutionary Aeron office chair). Neuroscience shows that when developing something radically different, allowing people to pre-experience it, by, for example, imagining it vividly, can lead to a better analysis of the innovation’s true value.

Experiments can also be driven by the collection and analysis of data to test an array of hypotheses. This is the process by which, in the third century BC, Greek scholar Eratosthenes calculated, reasonably accurately, how big the Earth was. More prosaically, this approach helps car shopping website Edmunds test various customer-driven hypotheses on a daily basis.

Organisations that embrace experimentation can expect to improve their decision-making, and do so on a sustainable basis. This is because the decision-making process itself exposes a whole series of cognitive biases that affect, and probably impair, our judgement without us realising it. Jeanne Liedtka, professor of business administration at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, says the only way to counter these biases is to use experiments as part of a scientific, hypothesis-driven approach to management.

If the gains are so obvious, why are many organisations reluctant to do this?

The problem with instinct, intuition and experience

Many CEOs, especially those with an entrepreneurial mindset, operate on the principle that, through instinct, intuition and experience, they just know what customers want and/or need. Indeed, they can often highlight past successes to prove their point. Liedtka calls this bias the “egocentric empathy gap”. Because we project our thoughts, preferences and behaviours onto other people, we assume we are right and yet, as she says: “Even venture capitalists, whose living depends on investing in the right businesses, typically get it right only 20% of the time.”

Neuroscience also tells us that we are hardwired to fear uncertainty and experiments, as, by their very nature, they create uncertainty both in terms of outcomes and timelines. With the growing pressure to meet quarterly targets – and the tech sector narrowing the timeframe for ‘speed to market’ to three from six months – any delays in executing a new strategy, product, service or marketing campaign can make senior managers fret.

Is it better to be curious than decisive?

There is also the matter of control. There is always a risk that an experiment’s results will contradict sacred cows and refute the assumptions made by the kind of CEO who effectively operates on the basis of ‘My way or the highway’. For Tim Ogilvie, founder of the innovation consultancy Peer Insight, this aversion to experimenting is, in part, a consequence of the way we train our leaders:

“If you think about it, we have traditionally coached managers to be decisive, when we should probably be coaching them to be curious.”

Curiosity can be liberating but it can also disrupt the status quo and challenge established behavioural norms about the way decisions are made.

As Liedtka observes: “Newton focused on the creative generation of alternate hypotheses, which could be validated or refuted by experimentation. This method – whether it involves physical experiments, or the collection and analysis of data – remains foreign to many managers, whose decision-making is based on a linear method in which the problem is defined, a comprehensive set of solutions is generated and evaluated, and the most promising option is then selected.”

This selection is influenced by all kinds of biases. When we try and imagine the future, we tend to base it on the present, a projection bias that makes it harder for us to achieve such breakthrough innovations as the iPhone, the personal computer and the Model T Ford car. Worse still, because many of transformational innovations are hard to imagine, we tend to undervalue them. “Defining problems in obvious, conventional ways tends, not surprisingly, to lead to obvious, conventional innovations. Asking a more interesting question can help teams discover more interesting ideas,” says Liedtka.

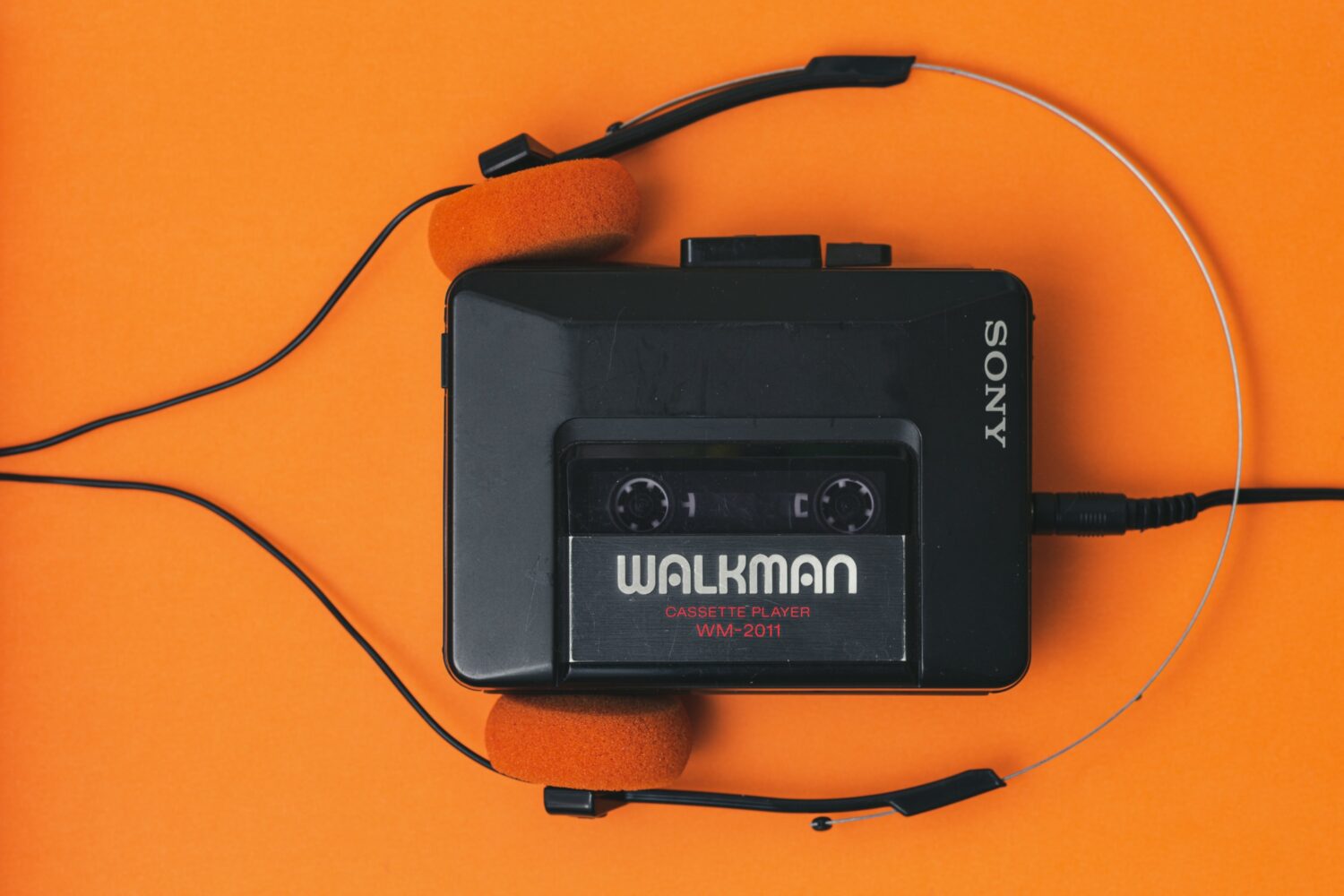

The market research ahead of the launch of the ground-breaking Sony Walkman in 1979 shows consumers can struggle to make an imaginative leap too. Focus groups were largely indifferent to the idea, with one particularly hostile consumer asking: “Why would I want to walk around with music playing in my head?”

Navigating this process can be tricky. Some teams may get hung-up on investigating the problem, while other, more action-oriented groups may hurtle towards a conventional solution. Managing this challenge can become especially problematic when the competitive threat – real or perceived – is factored in. “The greatest mistake you can make when launching a new product or service is not being second in the market,” says Ogilvie. “The greatest, most expensive mistake you can make is investing all that time and money in a product or service that nobody wants. Nobody wants to end up in a situation where they’re saying: ‘I wish we’d known what our customers thought in week two, not week 52’.”

Even those companies that recognise the need to obtain real-world feedback often settle for focus groups with, Ogilvie says, predictably mixed results: “What people say they do, and what they actually do are two different kinds of data. They’re both valid, but we know that people struggle to accurately describe their existing behaviour, which means they cannot always tell you what they want, let alone predict what they will want in future.”

“If you ask someone whether they will do x or y, they are socially conditioned to tell you what they think you want to hear. It’s human nature. For example, if I say ‘Do you like this flavour of ice cream?’ they are inclined to say yes. I might then conclude they will buy it. But we would have a more accurate picture if we tested the market by putting a small sample on sale. We could then prove or disprove the appeal of our new ice cream by analysing the ‘do data’.”

The strongest bias of all

One of the most common biases affects how we manage the information we have collected. Liedtka says: “We search for and favour the data that supports our favourite solution and find it hard to even recognise any data that challenges that. This predisposition is so strong that even when this bias is pointed out to a decision-maker, they often fail to correct it.” Sometimes this bias is a matter of attention. We focus more intensely on the data we agree with. This tendency is reinforced by what she calls the ‘Endowment Effect’ – our tendency to become so attached to our early ideas that giving them up is more painful than the pleasure we get from devising a new, improved solution.

The other advantage of hypotheses-driven management is that organisations are less likely to become so deeply wedded to the first solution they adopt. It is too easy, as Ogilvie says, for businesses to decide they must proceed to market because they have already invested $100, 000 in a project. McDonald’s customer experience design department tries to avoid sunk cost syndrome with a grounded, pragmatic approach to decision-making based, Ogilvie says, on three core principles: set audacious goals; share the product at “good enough” and let others – in other words, the target customer – validate.

When imperfection is perfect

The key is not to present people with a prototype that feels like a fait accompli. A prototype that looks incomplete, Ogilvie says, implicitly gives users permission to intervene, propose and modify. A physical prototype can help innovators avoid the ‘say/do’ data trap. Rather than asking people questions – which often equates to leading the witness – companies can let users discover a prototype, walk around it, touch it and construct their own narrative.

What exactly do we mean by unfinished? Here are three American examples:

- Kaiser Pharmaceutical tested a new medical office design by hanging sheets from ceilings to mark future walls and invited staff to suggest how these spaces could be improved.

- When Monash Health launched a new telemedicine service for vulnerable patients at home, it did not build a digital prototype but walked managers and policy makers through a series of detailed storyboards.

- David Jarrett, a partner at accountancy firm Crowe Horwath, likes to exchange ‘cartoons’ with clients after just two days of development work.

The paradoxical premise behind prototyping is that sometimes, when innovating, you need to slow down to speed up. The right prototype can help teams avoid such common mistakes as making things too complex too soon, or persisting too long with an inherently weak idea. Liedtka admits it is easier to prototype a new toothbrush than a new business model, but the process can, she says, still help companies analyse the likely effects of a new strategy or plan before it is implemented.

Experimenting can also help overcome one of the most common, yet overlooked, management failures: an organisation’s inability to see the world as it really is, not as its leaders would like it to be. In organisations with dysfunctional internal politics, experiments have the ability to speak truth to power – as long as those in power care to listen.

“If we start with the creative question ‘What if?’ and test our proposition with ’If x, then y’, and bring all the relevant data to bear, we can, repeated over time, pose ever-improving hypotheses, while retaining the ability to explore new ideas,” says Liedtka, “adapting even at a very late stage.”

This does not, she cautions, mean that experimenting is a chaotic process. Structure is essential. She says that experiments should be conducted with the same rigour with which companies have, in the past 20 years, embraced Total Quality Management (TQM) – making quality something that businesses can measure, manage and improve.

Before that, Liedtka says, quality was an amorphous and elusive concept in corporate Europe and North America and, when it became the domain of a committee of technical experts, could actively discourage innovation. The textbook example of this danger is Eastman Kodak. It recognised the threat posed by digital film in the late 1970s but, persuaded by technicians that consumers would never accept digital’s inferior quality, spent much of the next decade investing to enhance the quality of traditional film.

The cost of not experimenting – and of bad experiments

All it would have taken for Kodak to prove or disprove the experts’ verdict was to stage some experiments. Ironically, almost half a century earlier, the company’s founder George Eastman had ignored similar qualms about quality to champion colour film with the launch of Kodachrome in 1935.

By contrast, Coke seemed to take the bull by the horns when, after spending more than $4m on market research, it launched New Coke in 1985, in a move designed to reverse its declining market share. The problem with the soft drinks giant’s experiments, Liedtka says, is that it was not testing a provable hypothesis and also testing for the wrong things. “They extensively blind taste tested the product (with almost 200, 000 people) and it tasted better to almost everybody. But to one particular and important group of consumers – very loyal, high consuming drinkers – it wasn’t about a single taste.”

“It’s not clear whether these drinkers were too emotionally attached to the classic brand, or found New Coke too sweet when consumed frequently, but New Coke failed because the experiment only tested one dimension of a product – taste – and ignored differences between consumers. A proper test would have identified the particular group of consumers they needed to test it on and what the benefits to these drinkers would be,” she adds. Ultimately, Coke’s leaders fell foul of a phenomenon Liedtka calls the ‘focus illusion’ – a “tendency to overestimate the effect of one factor at the expense of others”. In this case, Coca Cola overestimated the importance of taste.

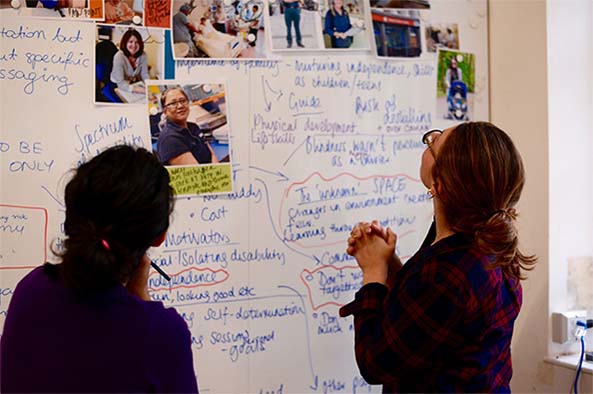

In documenting the work with DK&A on a co-creation customer service project with South Western Railway, Liedtka applied a four-stage model to ensure that the prototyping process had a clear structure:

- Learn customers’ wants and needs.

- Build a prototype based on those needs.

- Test that prototype with the target audience.

- Learn from audience feedback and improve the prototype.

Other structural models are available – some have three stages, others five – but they all start with empathetic listening which helps the organisation define a problem, build a prototype to resolve that problem, test it and use the target audience’s insights to refine the prototype. As Ogilvie says:

“It doesn’t necessarily take long to experiment. There is a saying in management consultancy: Will the dog eat the dog food?. The only way to find that out is to experiment. Often, the most effective experiment is to put a small sample out there. Consumers are savvy enough to understand if you say: ‘Thanks for taking part in our beta test, but we have decided not to proceed with the product’.”

CEOs could improve their decision-making by seeing each experiment as an opportunity to not to prove their hypothesis, but to improve it – and to recognise the possibility that the most effective way to improve their hypothesis is to disprove it.”

Why not make innovation easier?

Innovating is not easy. Depending on which statistics you believe, between 70% and 95% of product launches fail. Many innovations don’t even make it that far. In the modern corporation, there are so many places where a good idea can die: on a spreadsheet in the finance department; in a political trade-off in the boardroom and even, as the Walkman shows, in market research. Yet organisations can stop making innovation unnecessarily hard for themselves by correcting the many cognitive biases that impair their decision-making. And, there is a volume of research to suggest that the most effective method of doing that is experimenting.

On one of her research trips into corporate America, Liedtka was intrigued to meet a product development manager at a large chemical company who, she says, “had become a legend because he had the reputation of getting nine out of ten calls right”. In conversation, the surprising secret of his success was revealed. “It soon became apparent that what everyone else in the company regarded as a nine-out-of-ten success rate was actually something more like nine out of a hundred. He had become so adept at hypothesis-driven management that he could kill ninety of them at such an early stage that no one outside the department realised an experiment was taking place.” Imagine how much value your organisation could create – and how much money it could save – if you had managers like that in every department.