by Chris Howroyd — Oct 21, 2016

How can design thinking help improve public health services? Design Thinking coach Chris Howroyd tells the story of SH:24 and how design thinking led to this revolutionary new online sexual health service and a better experience for patients. SH:24 has been nominated for a Designs of the Year Award 2016 by the UK Design Museum.

5 years ago, you couldn’t walk past a funder or commissioner without hearing ‘outcomes approach.’ Most of the major grant funders in the UK moved to an outcomes approach – making it clear what changes they wanted to achieve through their funding, and being less prescriptive about how their grant-holders went about making those changes. They focused on the end result, the difference they wanted to make. Public sector commissioners, too, started to implement this approach, with varying degrees of success.

Today, however, some funders are starting to see the value of taking this a step further – moving from an outcomes model to a design-led approach. So what’s the difference?

Like an outcomes approach, design thinking doesn’t make any assumptions about how to deliver the change. Design thinking is based on iterative developments of a solution, rather than second-guessing the best way to do things. Unlike an outcomes approach, design thinking starts with a solid idea of the change it wants to make, but isn’t rigid about how to get there. Design thinking goes back to the problem, pulls it apart, and tries to understand it better, before testing and iterating solutions. The end result may not be what was originally envisaged, but will be stronger, informed by user insight which may challenge the original hypothesis about the problem and the way to arrive at the final solution.

SH:24 is a great example of how a proactive funder can use design thinking to drive meaningful innovation. This case study demonstrates the key principles of a design-led approach:

- Users at the heart of service design

- Iterative development and rapid testing of assumptions

- Continuous improvement

- Collaboration and systems thinking

The proposal

In 2011, Dr Gillian Holdsworth, a senior consultant in public health at Southwark and Lambeth Joint Public Health Department, and Dr Paula Baraitser, a senior consultant in sexual health at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, approached James Murray, Head of Funding at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity with a proposal to revolutionise sexual health services in Southwark and Lambeth, two areas in south London with some of the highest sexually transmitted infections (STI) rates in Europe. Sexual health budgets were (and still are) under immense pressure, and STI rates were increasing. A radical solution is needed and quickly.

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity is a dynamic funder, acting as a catalyst to tackle major health and care issues in the London boroughs of Southwark and Lambeth.

The original SH:24 proposal was ambitious – improve patient experience and encourage self-management, reduce costs, reduce waiting times, and improve access to sexual health services, all through an online service. Users would be able to order an STI test kit online, take samples themselves at home, return their samples and get their results by text message. Users who did not need treatment would never have to visit a clinic, freeing up clinic time to treat those who did. On top of this, SH:24 would offer a holistic sexual health service, including online access to contraception, remote chlamydia treatment, partner notification, information and support.

The Charity was interested – here was a proposal to tackle a major local issue, from a team of highly experienced public health professionals who were passionate about making services better for their local population. Yet this was a big ask, a significant investment in an untested concept. This proposal took a waterfall approach to IT development – though based on thorough research, the proposal relied on a complete build before market launch. Bearing in mind that SH:24 is a clinical service, requiring significant information governance, as well as a discreet, easy online experience for the user, and a seamless interface between user, labs, and clinics, the risk of creating something that wasn’t fit for purpose was high.

The Charity wanted this to work, and they’d had some previous experience of a design-led approach through working with the Design Council on initiatives like the Knee High Design Challenge, tackling big health issues through a process of divergent and convergent thinking.

So they asked SH:24 to work with the Design Council to redesign the proposal, injecting some design-thinking to reduce risk and cost of the service development. This is where I came in (as the then Head of Health at the Design Council), and together we created a proposal that the Charity was happy with. Unfortunately, just as the funding was secured, I had moved up to Scotland with my wife and young son, but the opportunity to develop the SH:24 service was too exciting to pass up, so my poor wife had to put up with many nights alone with the baby while I caught the sleeper up and down between Glasgow and London.

The design process

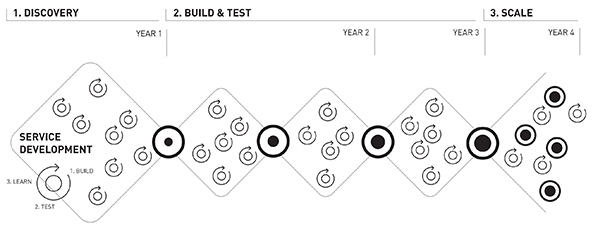

SH:24 used a combination of methodologies of design thinking, agile and lean (which are all cousins in my opinion) to rapidly prototype and iterate the service. Lean theory tells us to achieve as much as possible, as quickly and cheaply as possible, through the build-test-learn approach, while agile allows for the unexpected by advocating incremental change.

After gathering rich user insight to better understand the problem and the current situation (days spent observing and talking to patients and staff in clinics, in the queues outside the clinic, and in the labs), we developed a minimum viable product (MVP) – a very basic version of the service that would allow users to order a test kit, return their samples, and get results and notifications by text messages.

We prototyped the end-to-end service no less than 17 times with users* before launching a live beta. The learning was invaluable – we tested 12 fundamental assumptions, starting with the most basic:

People want [and will use] an online STI testing service’ through to some more nuanced features, e.g. ‘People want an online account to access their results and sexual health history.

*When I say user, I don’t just mean the person ordering the test kit. Users are anyone who comes into contact with the service, from the individual getting tested, to the clinic receptionist, to the clinician, to the lab specialist. The system doesn’t work if it doesn’t work for everyone.

Continuous optimisation

User-led testing hasn’t stopped after launch. We’re continuously improving the service through user feedback; we worked in partnership with clinics to develop a click and collect service so that people could order in-clinic on an iPad and pick-up a test kit immediately.

And we’re only half way through our development – we’ve launched MVP #1 (online STI testing and results notification) and MVP #2 (sexual health support), and are well into development for MVP #3 and #4 (chlamydia treatment and oral contraception).

Managing risk

SH:24 has been one of the most challenging projects I’ve worked on. We’re dealing with multiple touchpoints and interfaces – between SH:24 and our labs, between users and clinics, between users and the service – and diverse expectations and needs. We’ve had to balance these expectations, optimising the front end (the public facing website) for service users, while optimising the back end (the admin portal and notification process) for clinicians and clinic staff. There was also a cultural challenge of mobilising a ‘virtual’ service in parallel with the existing service; naturally, some people see this as a threat to their jobs and their skills.

Users want the service to be quick, discreet and confidential, trusting us to offer the same level of care that they’d get in an NHS clinic. If the process doesn’t work for them, they’ll not engage with it or they’ll leave.

Commissioners need us to be efficient and secure, reducing costs of STI treatment while migrating asymptomatic people out of clinics and into self-management. And everything needs to be done on time, securely and with extreme attention to detail. We test for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV and syphilis. We don’t want to get it wrong. And of course there’s a risk for the funder –backing a new approach to dealing with potentially very serious health issues.

The only way to overcome these kind of risks is to involve users at every step. A design-led approach enables this, and allows us to both learn about and manage risk. One of our biggest risks was potential cliff edges – people dropping out of the ordering or testing process because they found it too complicated or difficult, or couldn’t get the support they needed.

We’ve had over 28,000 orders since launch in March 2015. 96% of users who start the order process complete it in under 3 minutes, and 76% of those who order a kit return it with their samples (compared to an average 44% from the National HIV screening programme). We’ve had over 5000 texts conversations with users looking for support. We’ve learnt from every one of these interactions, and have now launched the service in five more regions.

Another obvious risk is that of incorrect diagnosis, or poor quality of advice or support. All of our information and advice is reviewed by clinicians (users themselves), and our incremental development allowed us to iterate the interactions between the lab and our data management system, allowing us to very quickly identify issues or inconsistencies.

The result

James Murray, Head of Funding at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, gave me this feedback:

“From a funder’s perspective SH:24 feels different to many of our projects. Encouraging a design led approach made sense for a project developing a “digital” service, but it has made a more fundamental difference to how the service develops and how we manage our funding. User consultation or service co-production remains an area of weakness in the health sector. The design methodology used by SH:24 has had an impact far beyond digital development. For example, it has worked with users to rethink how home-testing kits are used and as a consequence significantly increased the proportion of kits that users successfully complete and return. It also offers a clear timeline for project development, and functional milestones as breakpoints to assess progress and decide whether to continue the intervention.

SH:24 has been particularly successful in incorporating an evaluation method that can work alongside a design process. Finding this accommodation between research methods, which often require a locked down, ethically approved methodology, and design methods which demand iteration and adjustment, remains a key concern as we seek to promote greater use of design methods.”

Ultimately, design thinking has allowed us to learn from users at every step, creating a better user experience at all touchpoints within the service, from the moment that someone opens our website on their mobile phone, to the moment they walk into a clinic and show their SH:24 code to the receptionist for fast-tracked treatment.

Funders like Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity want to work with and for the communities they hope to benefit; a design-led approach allows them to engage and collaborate with users involving them at every stage of the journey towards a greater social impact.