by David Kester — May 27, 2021

For the launch of our new Responsible Revolutions initiative, founder and director David Kester talks through what led us here and why the world needs innovators now, more than ever.

Recently I have been reading and studying the origins and habits of human innovation. My interest is the scale and scope of the change management that businesses, organisations, and nations now face. It is unparalleled.

Just to avoid extinction, we have to…

- Kick our addiction to fossil fuels

- Run the world from alternative energy sources

- Re-design our business models to be circular

- Eliminate pollutants to land, air and sea

- Get to net Zero

- Stay fair

- Do it everywhere

- Now or else!

Anthropologists, like Joseph Henrich (Professor of Evolutionary Biology at Harvard) reveal that we can learn loads from looking back over the history and the cultural evolution of successful societies. The behaviours that have made certain societies thrive and innovate (and others not) hold some answers to how we tackle the exciting, daunting, wicked, existential and ultimately everyday challenges of the climate decade.

Can you read the following? “Am Anfang schuf Gott Himmel und Erde”

You may recognise that it’s the opening phrase of Genesis as written in the Lutheran bible that spread like wildfire across Europe in the 16th century. But did you know that this first printed bible, authored amongst others by Martin Luther, altered our human brain function?

Amongst a range of changes to your brain, literacy gives you:

- A thickened corpus callosum – the information high-way that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain

- An altered prefrontal cortex involved in language production

- Diminished ability to identify faces

Henrich’s et al have quantified the impact of literacy on Europeans and charted its effects as it spread out from Wittenberg in 1534 radiating like a pebble dropped in a pond. For every 100km travelled from Witttenberg the percentage of protestants dropped by 10%.

There are two important points to make. First, as we humans innovate and evolve culturally our psychology changes. Let me illustrate with a second example.

As humankind shifted from nomadic living to agricultural living and later urban living, so static markets evolved. And markets changed our psychology. The closer and more exposure you have to a market, the more likely you are to trust strangers. What psychologists refer to as impersonal trust. While the market economy sometimes gets a bad rep, it is in fact causally related to growth in trust between peoples and outside of clans and kinship groups.

The second point to make is that these innovations – like printing, or the computer, or vaccines – develop and spread through the combining and mixing of people, knowledge and skills. Not through the extraordinary talents of exceptional individuals.

Historians and storytellers make the milestone innovations of humankind memorable by attributing them to individuals. But the myth of the lone innovator belies a more important fundamental truth. More often than not, discoveries occur in many places and their application as innovation is always in the hands of collaborating groups.

The old adage that success has many parents – is in fact true

The Lutheran bible was the work of many people. Interestingly, Martin Luther also learned the idea of soft metals from his Dad who worked in the Mainz mint. Luther’s version wouldn’t have spread without the invention of moveable type by Johanes Gutenberg.

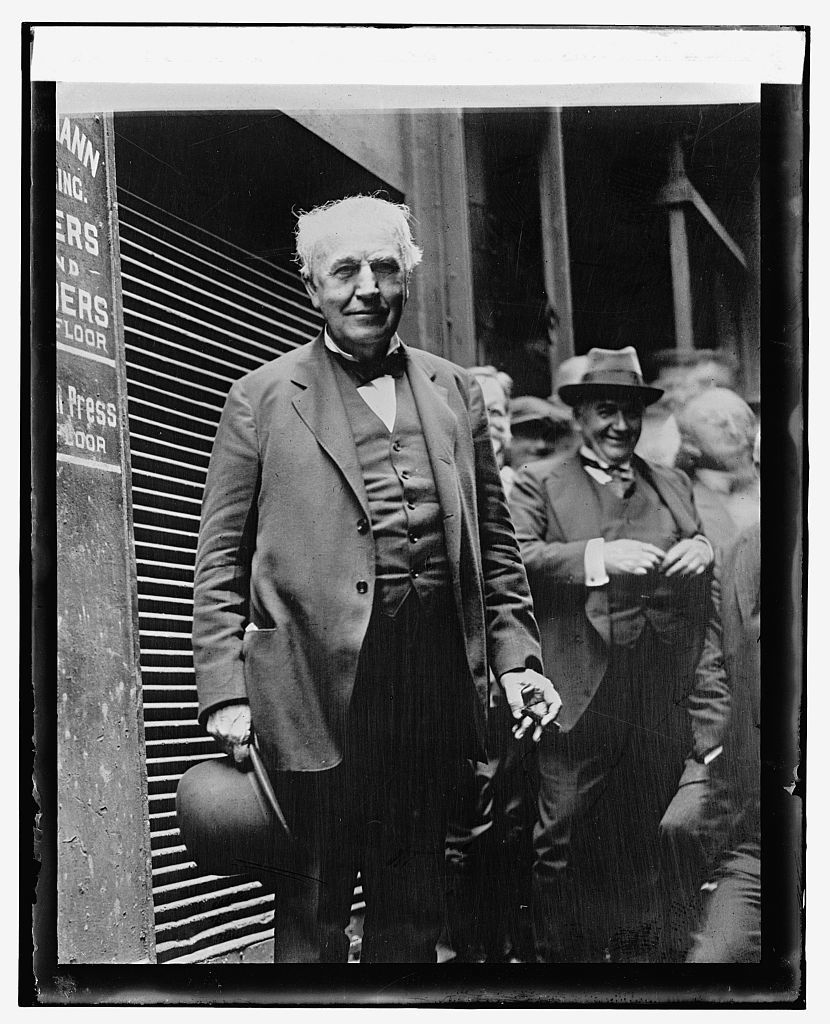

The very symbol of having a great idea – the lightbulb is credited to Thomas Edison in 1879. But you can trace the cumulative process of this great invention to the Scot Archibald Spencer in 1743 and to the English physicist Joseph Swan. Not to mention the fact that Edison’s work was forged in the crucible of one of the very first R&D labs at Menlo Park, where many experts and scientists collaborated.

As designers we are the humble midwives of innovation

We foster creativity – the generation of ideas – and we help turn ideas into practical innovation around the needs of users. Our processes and methods make it possible to codify the approach, replicate it, and educate others. Design thinking, of course, can be taught and is transferable as a management approach to accelerating innovation. But tools and techniques are like clothing and training regimes to athletes. Alone they don’t win the race.

Human history shows us that it is deep in our psychologies and cultures that we can find the big enablers of innovation. The cultural and psychological drivers trump techniques and methods every time. It is, for instance, the trust quotient that enables specialists and experts from many disciplines to come together, combine their know-how, and develop world-changing ideas.

Now more than ever – in this new decade of climate action – we will need not just the creativity to generate ideas, but the cultures of collaboration that underpin the design of the new services, business models and systems that will sustain us.

We need whole armies of innovators in all our businesses to do things more radically and faster than ever. Even the language of innovation needs to change. Innovation or even transformation is inadequate to express the sense rapid action that a new young generation are urgently demanding.

Our goal should be to create Responsible Revolutions. Responsible meaning: Moral accountability.

Revolutions from the dictionary definition: Instances of great change.

This is the innovators’ goal…and our vision.

Creating Responsible Revolutions.

For further reading on anthropology and innovation, David would recommend the work of Professor Joseph Henrich. His recent book, The Weirdest People in the World, inspired this article and provides a detailed evidenced guide to the development of western society.