The workshop is changing. Everything we once took for granted has dramatically shifted, and their future suddenly looks radically different. What’s next?

On this note, Design Thinkers Academy London co-founder David Kester notes, “this doesn’t have to be a negative. There is far more change to come and we have to see technology as our friend that can help humanise the virtual space.” This is easier said than done and if the virtual workshop is to deliver the same kind of experience as an in-person workshop, we need a whole new kind of innovation.

Reinventing work – and the workshop

One person who is driving this change is Arne van Oosterom, our Associate Creative Director at DK&A and the Design Thinkers Academy London. A natural contrarian, based in Haarlem in northern Holland, Arne founded the Design Thinkers Group in 2006 and works with governments, start-ups and companies such as Bosch, Coca-Cola, L’Oréal, SAP and Under Armour. As he discusses on a recent episode of our Design Thinkers Podcast, he was also a tutor on the Design Sprint Camp on sustainable innovation which coincided with the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow late last year.

As a workshop facilitator, leadership trainer and design thinker, Arne had hosted workshops around the world. Back then he took his relentless globetrotting for granted –“I thought nothing of going to New York for three days to give a ten-minute keynote speech at a conference – but in the past three years, he has had to reinvent his job.

“I suddenly had to ask myself – how do you translate workshops into the virtual sphere? How can they can still be engaging and fun when delivered online?”

So Arne innovated. With no guide as to how best to proceed he did what design thinkers do best: prototyped and tested his ideas. First he converted two rooms in his house into studios; then he added a green screen and combined tech hardware with softwares such as MmHmm to create a richer workshop experience. “I wanted to show that virtual workshops could deliver something fresh that people remember and engage with.”

Arne quickly began to understand the real benefits of the virtual world. “Looking back, the changes were already happening but the pandemic accelerated them,” says Arne. “Suddenly, workshops didn’t need to involve months of planning and the coordination of flights, accommodation and diaries. They could happen online, cost much less to run and be more inclusive and accessible because they were open to anyone across time zones.” Just as critically, he adds, they could now be managed so that they are much kinder to the environment.

At first, he says, many people found the change jarring. “At the start, you might have 60-70% of people wondering whether they could be seen and/or heard and whether they were using the technology correctly,” he says. “Two years later, I’d say that maybe 10% of participants have these concerns. We’ve gone from wrestling with platforms like Zoom, Teams and Google Hangout to using these professional microphones and cameras, green screens, virtual whiteboards and online stickies – and it’s making a big difference.”

The online attention deficit

This is not to say the change was seamless. The transition was hampered by a phenomenon the media dubbed ‘Zoom fatigue’. “People made the mistake of assuming that we experience online time in the same way as we do real time and it’s completely different,” says Arne. “You might be able to workshop all morning or all afternoon in the same physical space but you can’t online. It’s just too tiring.”

The issue of how we, as a species, pay attention is complicated. The oft-quoted statistic that we have an attention span of just eight seconds has been thoroughly debunked. Psychologists argue that such ‘averages’ are meaningless because a host of variables – from personality types and locations to the task we are focusing on –can affect our attention levels.

What we do know is that our brains work harder online. For a start, many of us are uncomfortable being on camera which makes us more self-aware and wondering how other participants perceive us. It takes more effort to decipher the non-verbal cues – particularly facial impressions and body language – which studies show actually have a bigger influence on how we communicate with people than what they say. In our new home working spaces, it is easy to be distracted by the fear that, even if the technology behaves itself, a cat or a child might not.

Such factors may explain why some researchers argue that more – and better – creative ideas emerge in in-person workshops. The evidence is inconclusive and may simply reflect the fact that most of us have only regularly experienced online workshops – as participants, contributors, facilitators or organisers – in the past three years. The internet is awash with ideas of how to improve the quality of remote workshops yet for Arne one commonly overlooked factor is trust.

“People need to feel there is a safe space in which they can express their ideas,” he says. “If you’re in the same room, that process begins with the rituals that occur before the workshop starts – being told where you can hang your coat and get a coffee, socialising with other people, this all helps quietly build trust. The facilitator reinforces that process by emphasising the ground rules, the most important of which are that there are no bad or stupid ideas and that it is perfectly acceptable to say you don’t know.” That trust can, he admits, be harder to build online but it can be done.

Change cannot be outsourced

The decisive competitive advantage online workshops have, Arne says, is that they help organisations manage and implement change more effectively. “A workshop is not the purpose, in itself, it exists to help an organisation achieve a purpose, whether that is a new business strategy, marketing campaign or product. In the past, these workshops were separate from work and not integrated into it. People would go to these events, get fired up, agree it had been a great workshop but then, when they went back to work, nothing happened.”

As the euphoria evaporates, he says, so does the momentum for change.

Let’s say the aim is to make the company more customer centric – quite a common goal – then the focus is inevitably on the customer but, once the workshop is over, the first challenge has nothing to do with the customer, it’s about change management. Can you implement the organisational changes you need to make?

Achieving change is never easy – as the American management thinker Rosabeth Moss Kanter observed: “Everything looks like failure in the middle” – but being able to quickly, economically and (relatively simply) follow up on the findings of the first workshop can maintain momentum. That way, the recommendations do not languish in limbo until the next workshop can be organised in a few months’ time. One other significant benefit of online workshops is that, as participation is not restricted by travel costs, everyone who has a stake in the purpose can contribute.

Many companies use external workshop facilitators to guarantee an open, creative debate. Yet ultimately, Arne says, it is the organisation’s responsibility to implement change:

“You cannot outsource empathy, you cannot outsource innovation and you cannot outsource systemic thinking, you have to do it yourself.”

To the metaverse and beyond!

The enforced reinvention of the workshop will not stop. If anything, it is likely to accelerate, driven by such emerging technologies as virtual reality, augmented reality and artificial intelligence. In Wunderman Thompson’s 2022 report, The Future 100, the media agency predicts: “A new digital era is on the horizon, as the metaverse evolves from a sci-fi concept to a reality. Virtual worlds where people can gather, create, buy and sell, socialise, live and work are becoming new hangouts. Technology that allows for advanced avatars, virtual transportation, and NFT marketplaces is revolutionising virtual engagement.”

Such hyperbole makes it sound as if the metaverse will arrive sometime in the next ten days. Yet some experts are sceptical. As Sarah Fischer, Axios media editor, cautioned recently: “We’re still many years away from any sort of shared 3D reality achieving the kind of prevalence and utility of basic internet services today.” Not least, as Fischer notes, because barely any thought has been given to the software standards that would enable competing systems to talk to each other.

If there is one lesson we can take from the history of technological advances it is that such transitions are seldom seamless. The metaverse will seem utopian to some and dystopian to others. In a hybrid workplace, many of us will feel uneasy about our technological skills, the capability of our internet service, the idea of being virtually transported to a workshop and interacting with an avatar.

“Whatever can be done by technology will be done by technology,” says Arne. “Tasks that are repetitive, logical and sequential will be increasingly managed by technology. What technology – and AI – cannot do is imagine something that doesn’t exist, which is one of the things that we, the human race, do very well. As AI also can’t feel – or learn – emotions, it is hard to envisage it acquiring the soft skills that will become increasingly critical in the workplace of the future.” He also predicts that, definitions of expertise will change, and there will be a greater need for generalists which will be hard for AI “because it can’t make the serendipitous connections in the way we can.”

Back to the future?

Arne is no Luddite – far from it – but nor is he a technological triumphalist. The real question organisations should ask about the metaverse is not, he says, when, or how much, but why? “No organisation holds workshops for the sake of it – the aim is always to achieve a specific purpose – so the real question is whether a virtual workshop in the metaverse makes it more likely that that purpose will be achieved.”

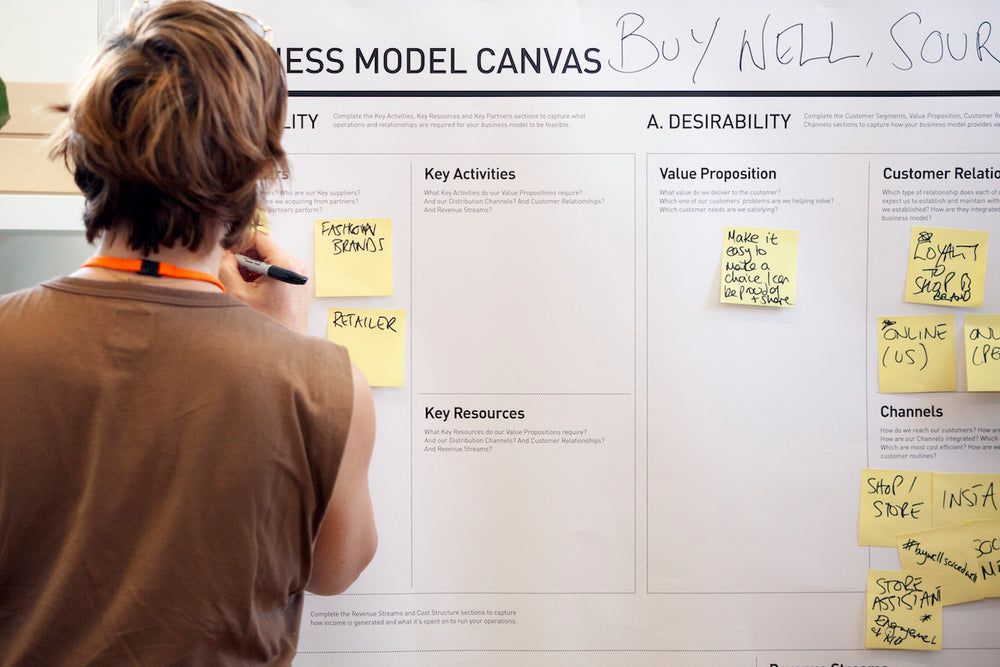

The underrated virtue of the old school workshop was that, in essence, we only needed three things to contribute: something to think with, something to write with and something to write on. After a few glitches, we have adjusted to the slightly more technically demanding world of online workshops. In a hybrid workplace, if the metaverse means that participation is restricted by status, cost or technological prowess, we will probably be forced, Arne implies, to reinvent the workshop all over again.

If you're interested in joining Arne on our upcoming FastTrack Design Thinking, or any of our other Design Thinking courses, get in touch.